Earth Sciences in Conversation: Andrew Walker

Our Earth Sciences in Conversation series explores the lives and careers of members of the Department, showing readers the people behind our world-leading research. For this issue we sat down with Andrew Walker, Associate Professor and Senior Research Fellow in Computational Geosciences, to learn more about his approach to teaching coding, the proudest moment of his career so far, and his favourite programming language…

Interview by Charlie Rex

What (or who) inspired you to get into Earth Sciences?

Originally, I think it was the breadth of science that you could study in a single subject. When I was looking at what subjects to study as a degree, I was doing Chemistry, Maths and Geology at A Level. I knew that in Earth Sciences I could do some biology, and some chemistry, and also some physics, and all of that was interesting to me. Plus, the fact it was applied science rather than just theoretical. Maybe it was also a small amount of procrastination on that decision making process!

It’s a little unusual to have studied Geology at A Level! What made you choose that option?

That was a long time ago! I started off with Maths, Chemistry and Physics, and wanted something to complement those choices. And I enjoyed Geography at GCSE, especially physical geography, as well as the sciences. So I took Earth Sciences as an additional subject and then ended up enjoying it more than I enjoyed Physics, which is sort of interesting considering the direction my career has taken [laughs]. I think that shows that maybe our decision making at 16 is not necessarily a particularly strong indicator of what we might end up doing later in life!

So having chosen to study Earth Sciences, what did your University journey look like?

I did an undergraduate degree in Geological Sciences at UCL as a four-year integrated masters – that was when four-year courses were a new concept, I think was I was the second year of entry. I really enjoyed it, especially my final year research project which was on mineral physics, and knew I wanted to do a PhD. I didn’t get very far in the standard PhD application process that happened around Christmas time, but then one of my advisors approached me just before Easter and asked if I was still looking for PhD because there was a project available at the Royal Institution. And I thought “yes, I am still interested in a PhD… what is the Royal Institution?”– it turns out it’s the organisation that runs the Christmas Lectures, and it has an associated research lab. I got a PhD in computational mineral physics.

You have had a fascinating career journey so far. Tell us about the different places you have worked.

After my PhD I quite conventionally started doing postdocs. I did one in Australia at the Australian National University, and then was looking for a follow-up position, and the one that looked the most interesting was in Cambridge. The project was working on the use of computers to enable research. Half the time I was working in my field of mineral science, and then the other half I was working with computer scientists to develop software and to move computation around the country. I then got a NERC postdoctoral fellowship for three years, which was largely based at UCL, looking at similar topics to my PhD. When that finished, I moved to Bristol and changed the direction of my research to global geophysics, away from the atomic scale, and learnt a bunch of new science, which I think was quite important for me receiving a NERC independent research fellowship. By that point I was at the senior end of when people get these five year IRFs, and had been knocking about the system for long enough to know how it worked, and used that to secure a position at Leeds. I went through the promotion process that led to a permanent academic position (as associate professor) and did some research, but also ended up running the undergraduate geophysics programme. Finally, I moved to Oxford to this role, which is not a standard academic job – I have research projects and graduate students, and I do a small amount of teaching, but I also look after the strategy of computational research in the Department. I’ve been here five years now.

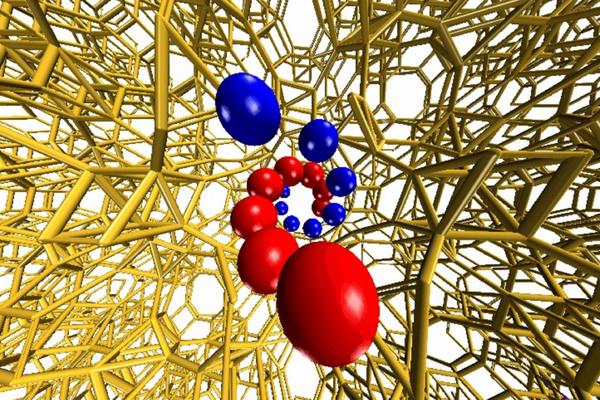

Example of atomic scale simulation. This image shows the structure of a screw dislocation in zeolite A extracted from the centre of an atomic scale model of about 250,000 atoms. The blue and red spheres represent a double helix of silicon atoms that form around the centre of the dislocation. This image was created from data in Andrew’s second PhD publication (Walker et al. 2004, Predicting the structure of screw dislocations in nanoporous materials, Nature Materials https://doi.org/10.1038/nmat1213.

When did you develop your interest and skills in computational methods?

It came into my research as part of my undergraduate project, and then it was a really key part of my PhD. I could write a computer programme before I went to university – that was a thing that happened in the 80s! So the idea of programming was not something that I learnt formally through my educational journey. My undergraduate project was using computers, and I did atomic scale simulations alongside lab work. Then once I got to my PhD, I very quickly saw the benefits of not having to do everything manually. I did a course alongside my PhD learning FORTRAN, an hour a week for a term. And then I learnt Perl on the tube on my commute into the lab – I read a chapter of a practice book each day and then when I arrived at work I would spend half an hour working through the accompanying exercises. Within three or four months I could programme that language well. The real deep dive came during my postdoc at Cambridge.

What’s your favourite programming language and why?

You can do some fun things in Perl that really confuse everybody! I wouldn't recommend it for anybody [laughs], but being able to write really terse Perl is fun. I’ve not used it for quite some time, but it's got some really clever defaults. It was developed by a linguist, and a lot of the syntax is just really clever, and designed for you to become fluent. Having said that, it does lead to really unmaintainable code! What’s actually important when you write a programme is for other people to read it, not the computer. So it’s kind of like me saying that my favourite language is something spoken by only a small proportion of the population, like Cornish – it’s not practical in everyday use, however much fun it might be to learn and use it.

What developments in computational geoscience do you think will happen in the next decade?

I think probably the biggest and most important change is around the training we provide to junior researchers – graduate students in particular – especially those who don’t see themselves as computational scientists, in how to take advantage of the most important tool for science, which is the computer. It’s about how we train them to make the most of computers – digital lab notebooks, automating data analysis, etc. These just open up so much more breadth in what you can tackle and the ways you can tackle it. I think that's probably the most important direction. It’s in the democratisation of research computing that the biggest change should – and will – be.

What are your thoughts on using AI in research?

I think we talk about two different things when we talk about AI. On the one hand, we're talking about the common use of large language models – for apparently everything! – and on the other we’re talking about developing our own more traditional machine learning models to help with tasks or to represent data. The interesting opportunity is the latter – thinking about what can we use machine learning algorithms for. You can use them as emulators for a more complicated or computationally expensive aspect of your calculation. By taking the difficult heart out of your calculation and replacing it with some machine learning tool that gives you the same answer in a way that’s much simpler, then you can do bigger or more simulations.

You introduce our undergraduates to programming as part of their first year maths course. What’s your favourite part of that process?

The way I teach is not like traditional lectures – we all sit down in the computer lab and I show programming in real time. I talk through what I’m doing and then have the students do short exercises to complement that. The thing I like most about teaching is when the learners can do something afterwards that they couldn’t do before. It’s more satisfying for me than “at the end of this session you will know how to answer an essay question”. It’s quite similar to fieldwork in a sense, that there’s a point where suddenly someone who couldn’t do something can do something. And that’s what I find most enjoyable about teaching.

A rubber duck is useful for teaching students how to find bugs in software. The idea is to explain the way the code works to somebody (or something, like a rubber duck) while reading the code. Students experience a moment of cogitative dissonance when what they read doesn’t match what they say, revealing the error. Andrew’s duck has lived on his desk since it was gifted to him during instructor training for The Carpentries and has helped many people debug their software.

How do you reassure students who haven’t had a lot of coding experience before?

I think the secret is for me to make mistakes. If I'm programming in front of 30 or 40 students, I'm going to make errors because I'm typing this stuff in from memory. It is quite challenging if you are a new student at university and you have to own up to not knowing how to do something. You can see why some people are resistant to that. What I can do is try my best to make that environment as conducive as possible to being able to say “yeah, I don’t understand this” or “I can’t do this” or “I’ve got this different solution”. That’s brilliant when it happens – some students come up with a completely different solution that works and we can have a conversation about it. I think an important part of teaching is being able to bring your students into a place where you can work through it together.

What motivates you as a researcher?

I think increasingly it's to do with who I work with, and the excitement of a shared exploration of something that you don't know. So when we're trying to tackle a problem, we don't have a clue what the answer is going to be, but we're going to go off and explore this unknown bit of science. It’s that shared intellectual endeavour that motivates me.

Do you have a favourite thing about working here in Oxford?

I like that Oxford is institutionally confident enough to trust the research staff and faculty to do the research they want to do. It lets the research drive the direction, and there is comparatively little top-down interference. At some institutions there are clusters of research which are excellent, but that means you end up constantly trying to make sure you’re inside that bubble, or accept there is a lack of resource for your work.

What is the proudest achievement in your career so far?

I remember publishing my first paper, that was a big deal. And not even the publishing necessarily, it was the getting to the point of the research during my PhD where I’d discovered something that nobody else knows. Looking back, it really mattered that I had gotten to the point of saying that I had an answer to the question I was trying to ask. It was this technically geeky thing about oxygen diffusion in olivine, but it was a real feeling of achievement.

What would you say to someone just starting out in computational geoscience research?

Career-wise I would say to choose what you want to do next because you want to, rather than because it leads to some potential thing in the future. And I think if you’re going to pick any area, really learn the methods. Properly spend time on it. During your PhD is probably the only time you are going to get to really master a methodology, and if you can do that it will always stand you in good stead to drive the method forward or apply the method in new directions. So really take the time to nail whatever your chosen tool is.

Your research involves Earth’s deep interior. Can you tell us why you think that’s so important to humankind?

It is predominantly processes inside the Earth that drive the surface processes that shape the planet. So if we want to understand where mountains come from, how we sustain a magnetic field and therefore have a habitable environment, how we have stability of liquid water on the surface for geological time, we need to understand how the planet works on larger scale. If we want to understand our planet then you can't ignore the vast majority of it. But I think also there's value in studying a subject because it's interesting. That is one of the things that makes us human, and that is in itself is worthy of having.

What’s your favourite piece of fiction (book, movie, TV show, song) that involves Earth Sciences?

I quite like Terry Pratchett's description in Discworld of how the Earth works – that we are whizzing along on a flat disc on the back of some elephants and a tortoise! We could get to explore Earth's deep interior by peering over the waterfall at the edge and looking underneath, because it's flat so you can look over and explore the inner workings.

Finally, tell us what are you currently working on?

So there's the Earth's inner core nucleation paradox, which we published on recently. So that's one aspect of what I'm doing, and another is actually a methodological problem around how to perform research computation such that you minimise the amount of carbon dioxide emitted to enable it. That's a very, very different project, but it's quite fun to work on. In a country like the UK the amount of carbon dioxide released to generate a kilowatt of electricity changes by a couple of orders magnitude from day-to-day. But if you can use electricity when it's windy, suddenly the electricity is almost free of carbon emissions. I've done some work over the last couple of years on that scheduling problem. We have been thinking about how you schedule the compute so that it takes advantage of low carbon electricity. As well as a technical issue, like moving infrastructure around, there’s also some social science there, because you need to convince scientists that it’s ok to wait and run the simulation tomorrow.