Earth Sciences in Conversation: Darren Hillegonds

Our Earth Sciences in Conversation series explores the lives and careers of members of the Department, showing readers the people behind our world-leading research. For this issue we sat down with Darren Hillegonds, Research Fellow in Analytical Chemistry, to hear about his journey from Chemistry to Earth Sciences, his love of noble gases, and his involvement with the Paramount+ series The Agency.

Interview by Charlie Rex

What (or who) inspired you to get into Earth Sciences?

I didn't start out in Earth sciences – I was an analytical chemist to begin with. Originally, I wanted to do archaeology, but then when I got to grad school I ended up studying meteorites. I was working in a carbon-14 dating lab at the time, and we were taking meteorites that were found in Antarctica and measuring the amount of radiocarbon inside to date when it landed on Earth. So most of my thesis was on meteorites, and I think that’s where I learned to appreciate the study of the natural world.

Tell us about what you studied at University

Sure thing. I started out with an undergrad at the University of Michigan, and I studied chemistry and classical archaeology as a double major. After that, I ended up going to graduate school for chemistry. I would have dearly loved to study archaeology more, but even at the tender age of 20, I knew that chemistry was a bit more marketable in terms of finding a job one day! I went to graduate school at Purdue University in Indiana, which is one of the best analytical chemistry departments in the country. That's where I got into the meteorites, because my thesis advisor, Mike Lipschutz, was a kind of a bigwig in that field. There was also an AMS (accelerator mass spectrometry) lab, and that's where I was doing the radiocarbon work. At the time, I also branched out into biomedical research for the first time. That’s when I wrote my most cited paper – we implanted radiocarbon into an animal and then looked at how that distributed itself over time.

Where has your career taken you post-PhD?

When I finished my PhD, I decided to do a postdoc in calcium biomedical research at the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory in California, where they have one of the most prolific AMS laboratories in the world. We were using calcium-41, a very low dose radionuclide, to study bone metastasis. But doing research at a national lab is exceptionally expensive, and eventually the lab decided that they wanted to move the research into other areas. At that point a job working with noble gases opened up at Livermore; they needed somebody to manage their lab. The research was principally concerned with groundwater dating in California. I pursued that for a number of years and became a permanent employee, and then I got an e-mail from a colleague about an opportunity abroad, which I forwarded to my wife asking “what do you think about moving to Austria?” with a “haha” from me, thinking that would be nice but unrealistic. But it turned out I was fairly well suited to the role, and we did end up moving! I became a helium isotope mass spectrometry specialist at the International Atomic Energy Agency. I continued doing groundwater work but also started looking at longer half-life nuclides to date old water, such as krypton-81. And then at one point the lab manager here at Oxford successfully applied to work at the IAEA, which opened up the position I had now, so we essentially did a swap. I’ve been here nine years now, running the Noble Gas Lab with Professor Chris Ballentine.

Darren in his youth

We know you as a noble gas expert – was Livermore the first time in your career you worked with noble gases?

Yes – I'd never done any noble gas work prior to that. But there was a very experienced scientist, Carol Velsko, who took me under her wing, and she taught me how to do everything. And when I ran into inevitable problems with the machine, she would swoop in and help me fix everything. I am so very appreciative of the time that she spent with me. And I mean, I'm still learning. Every time I run an unknown sample from a new area, I learn something new.

You've experienced the US, European and UK higher education worlds – can you speak to the differences or similarities between those?

They aren’t that different, but obviously Oxford is really weird in terms of the way that you have tutorials as part of the education system! Because it’s the best university in the world, I sort of expected Oxford to be quite intense and egotistical, but what I found was the opposite. Everyone is very helpful and laid back, and you can always stop a professor in the hallway and have a chat. I really appreciate that. My experience in America was in a chemistry department, where they don’t necessarily have the same personality as earth scientists, especially earth scientists that do fieldwork. I think that camaraderie stays with people all the way through their careers, which makes them really nice people to work with.

You’ve spent a large portion of your career working with analytical techniques. Why do you find them so interesting?

If you don't make reliable measurements, then all the science you do with those measurements is unreliable too. So it's really critical to have measurements of the natural world which are extremely reliable – not just ‘pretty good’, but the highest level of reliability, so you can then build other areas of science on it. If, as analytical earth scientists, we don’t hold up our end of the bargain by making the best measurements, then the whole house of cards kind of falls down. So I’ve always been really interested in that aspect of it. Plus, it's very creative. Sometimes I'm in the middle of a measurement and I realise I’m about to lose the sample and I have 30 seconds to figure out what to do. You may not think science is exciting in this regard, but when you've got literally seconds to decide how to change the analysis or you're going to lose this irreplaceable sample, that can be exciting.

What is the most exciting sample you have ever analysed?

I think the most exciting sample I've ever measured was when I was working at Livermore in bone biology research. You can measure the rate of bone turnover by detecting the little bits of bone that end up in your urine or blood, but those methods have a lot of variability in them. You can have quite a difference in metastasis rate, but the signal reads as barely outside error. So we did a study with some colleagues in Zurich. They gave a number of subjects some bisphosphonate drugs that intentionally slow the rate of bone turnover. I remember sitting there late at night when the first measurements came through, and even within first 24 hours after the drug was given, the signals were already dropping like a rock – the change was super obvious. I was really pleased. I didn't even have to process the data, I could see the change from the raw signals.

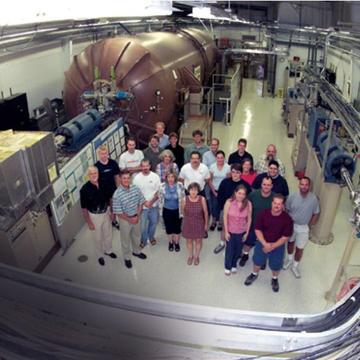

The AMS at Livermore, featuring Darren with blue hair

You have the opportunity to work with lots of DPhil students and other early career researchers in your role – what has that taught you?

A lot of them are very, very excited about the science, and that optimism is really nice to have. It’s also really fun to work with the students that seem to already know how to do research – like it’s innate. But sometimes we also get students who are more nervous or suffer from imposter syndrome, and it’s taught me how to support them. But all the students here are so lovely, so nice to work with, and very interested in learning.

What motivates you day-to-day as a researcher?

It takes a lot of work to get a lab like ours to run properly, and so when it is running, it’s very satisfying to come in make useful, reliable measurements. It’s so exciting to know you’re doing good science. On the other hand, it can be a bit soul crushing when nothing is working and you can’t figure out how things can be fixed, but in those times the global noble gas community is extremely helpful and supportive. I can contact any of the top people in the field with a question and they will be more than happy to help. It’s a very positive working community.

You had the opportunity to be involved when Paramount+ filmed here in the Department last year – can you tell us how you found working at the intersection of science and the creative industry?

I was never more excited to go into work than when the film crew was here! I think the thing that stuck with me about the Paramount+ filming was the enormous number of people operating as a well-oiled machine. There were like 200 people here, all in lockstep, which was super impressive. And it was such a great experience because we got to help the crew, and I got to be an extra on one of the days too. On the last day of filming my family came in and the crew welcomed them with open arms too. A really once in a lifetime kind of experience.

Darren in the Noble Gas Laboratory at the IAEA, Vienna

You are a harassment advisor and an active member of the EEDI Committee here in the Department. Why are you so passionate about supporting people in this way?

I like helping people around me, and I don’t like people not being happy. It’s great to have the opportunity to be a harassment advisor, and to be on the EEDI Committee. I’ve spent my life being very empathetic and I do like to try and understand how other people are feeling. Some students, especially fourth years, can feel a lot of pressure, and it’s nice to be able to sit down with them and talk through their challenges. It’s great that the Department has these opportunities for people to care for those around them.

Apart from the filming, what has been a highlight of working here in Oxford?

I think because I studied archaeology as an undergrad, I've always had a very deep and abiding interest in history. And being American, there’s not as much history there as there is in the UK. Walking past a building that's a thousand years older than my country has always been very interesting and amusing to me. I think just being around all of the history, and all of the amazing scientific discoveries that have occurred here and just being able to be a part of that is really cool. Being invited to the occasional formal dinner is really great too!

What would you say to someone just starting out as an Earth Scientist?

I would encourage them to pursue something that's interesting to them and that they are passionate about. You need to consider whether you can get a job in it later on, but that should definitely be secondary to enjoying what you're doing and the people you're around. It's going to be hard work, and you're going to have days where you’re unmotivated or stressed out. But if you enjoy it and value the relationships with your colleagues, you will be in a great place to be successful.

Darren with family in Vienna, whilst working at the IAEA

What developments in analytical methods do you think will happen in the next decade?

I think there's always going to be improvements in the quality and precision of the data. There's a researcher in Ireland who's doing similar work to what we're doing, but at an inhumanly high precision – like crazy precision – and he's able to answer questions that people haven't been able to ask before. We're also trying to integrate all of our analytical systems in the Department into one integrated facility, so that when a sample arrives, I can measure all the noble gas isotopes and then down the hallway we can do the elemental concentrations, and the stable isotope measurements, and other analyses all in one go. I think being able to integrate all of this data at good precision all at the same time on the same sample would be a great way to address questions that no one's ever addressed before.

What’s your favourite piece of fiction that involves Earth Sciences?

Can I say Lord of the Rings, because of Mount Doom? I question whether it would actually erupt the way it was depicted on the new television series, but I'm a chemist, so maybe it did!