Professor Mike Searle compiles a new “Geological map of the Greater Himalayan Ranges”

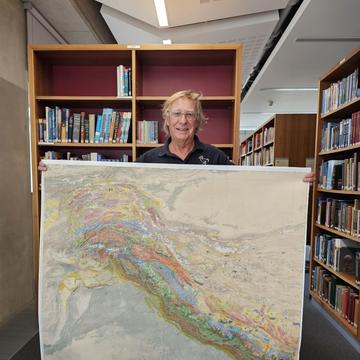

Mike Searle, Emeritus Professor at Oxford Earth Sciences and Honorary Associate at the Oxford University Museum of Natural History, holds the western sheet of the geological map

This summer Professor Mike Searle has carefully compiled a comprehensive new geological map of the entire Himalayas. By drawing on his own field experiences, and previously published maps by his research group and others across the world, Mike has brought together a wealth of knowledge about this fascinating mountain range, which is set for publication next year.

This mapping project represents the culmination of decades of research by Mike and his doctoral students who have created maps of different regions – but until now nobody has brought all this knowledge together. Over this summer, he has hand-drawn the spatial extents of around100 lithologies to create the first complete geological map of the Himalayas extending from the Afghanistan/Pakistan border in the west to the Myanmar Indo-Burman ranges in the east. The western sheet, which is close to completion, has taken six weeks to compile, and an eastern sheet is also underway.

“I have been thinking about this for years,” said Mike. “It’s an opportunity to bring together my field experience and all the information we have available to us. But it’s also a huge task, hand-drawing two giant maps. We need to decide if it will end up being over two metres long, or if we put them back-to-back!”

Mike has an unparalleled knowledge of Himalayan geology, having visited almost annually for over 40 years, since completing his PhD at the Open University in 1980. His love of climbing and mountaineering translated to a fascination with the area, which began whilst collecting tourmaline granites during his descent of Langtang Lirung.

What followed was a remarkable career studying the geology of the Himalayas across vast regions of northern India, northern Pakistan, Tibet and Nepal. Mike has trekked to Everest Base Camp on six occasions, and camped on the moraines of the Khumbu Glacier to map nearby. “It was always an incredible adventure. You need to climb to reach the best geology,” reflected Mike. “I feel fortunate to have spent time there before the numbers of climbers increased massively. But even then, coming back into camp always felt extremely busy compared to remote hiking off the trail to map the surrounding areas.”

“This process has allowed me to reflect on my many years working in this very special and important part of the world. It’s been great fun, incredibly worthwhile and a very therapeutic process. I’ve also found that it brings back great memories of the time I have spent trekking and climbing across the mountain range.”

- Professor Mike Searle

The published geological map of Pakistan (upper) and the eastern sheet of the geological map under development (lower)

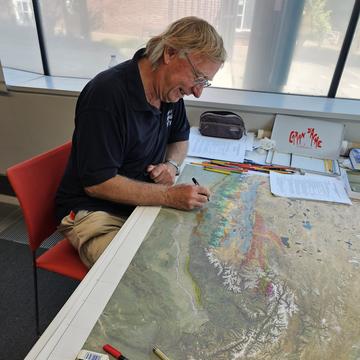

His experience observing the complexities of the geology first-hand has allowed him to carefully tie together maps created by his students and other geologists worldwide, as well as his own previous works. But whilst some areas are extremely well-mapped, it isn’t always a straightforward process, and he has had to make hard decisions about correlations and scales.

“There are some gaps in our knowledge – some areas of the Himalayas are extremely remote and others are covered in dense jungle where mapping is an impossible task,” said Mike. “In these cases, we need to interpret based on what has been mapped nearby. Some units are almost continuous all the way along the Himalayas, which helps – and reduces the number of colour pencils I need to use!”

There have also been some surprises during the process. Some critical areas are poorly mapped due to accessibility (both physically and politically) – including where the Nanga Parbat meets the Indus River, known for having the highest rock uplift rates in the world and one of the highest river incision rates, respectively. “But putting the map together at this scale has allowed me to link lots of areas, and has raised all sorts of new questions,” he added.

Professor Mike Searle making some additions to the eastern sheet

The Himalayas were formed around 65 million years ago by the head-on collision of the Indian tectonic plate into the Eurasian plate, which resulted in the orogenetic construction of the highest relief in the world. Alongside other superlatives – that it supplies fresh water for more than a fifth of the global population, accounts for a quarter of the global sedimentary budget and has the highest concentration of glaciers outside of the polar regions – it remains an incredibly active mountain belt. The 2015 Gorkha earthquake in Nepal was testament to the sort of geological hazards that can commonplace along the Himalaya. This new map will provide vital context for the area’s geological history, helping to understand current tectonic activity.

Once complete, Mike will hand over the map to his long-time colleague Marc St-Onge (Geological Survey of Canada), who alongside a team of draftsmen will create a digital copy of the map in Ottawa, Canada, which is set to be printed next summer by specialists at the Sorbonne Université in Paris.

Speaking of his ambitions for the map, Mike said “I hope that a copy appears on the wall of every Himalayan trekking hut, and every Earth Sciences Department! Geological maps are an incredible resource for teaching students. When you combine maps, cross sections and geochronological information you force people to think in 3D – and even 4D when you consider how the geology has evolved through time.”