Golden bugs: Spectacular new fossil arthropods preserved in fool’s gold

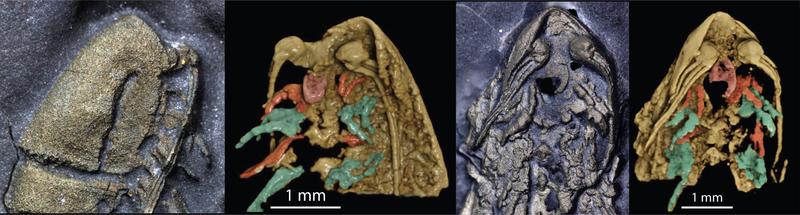

The holotype specimen of Lomankus edgecombei. Photograph at left, other images at right are 3D models from CT scanning. Credits: Luke Parry (photograph), Yu Liu, Ruixin Ran (3D models).

A team of researchers led by Associate Professor Luke Parry, Department of Earth Sciences, University of Oxford, have unveiled a new 450-million-year-old fossil arthropod (the group that contains spiders, centipedes and insects) from the Ordovician Period. The specimens, detailed in a new publication for the journal Current Biology, are spectacularly preserved in 3D by pyrite (fool’s gold), giving them a beautiful gold appearance.

The fossil was found at a site in New York State, USA that contains the famous “Beecher’s Trilobite Bed”; a layer of rock containing multiple trilobites with incredible preservation. Aside from trilobites, other kinds of organisms are much less common at this site, reflecting the rarity of this find.

The new fossil, named Lomankus edgecombei, after arthropod expert Greg Edgecombe of London’s Natural History Museum, belongs to a group called megacheirans, an iconic group of fossil arthropods with a large, modified leg (called a “great appendage”) at the front of their bodies that was used to capture prey. Megacheirans like Lomankus were very diverse during the Cambrian Period (538-485 million years ago) but were thought to be largely extinct by the Ordovician Period (485-443 million years ago), when this new fossil was preserved.

The animals preserved in Beecher’s Trilobite Bed lived in a hostile, low oxygen environment that allowed pyrite, commonly known as fool’s gold, to replace parts of their bodies after they were buried in sediment, resulting in golden 3D fossils. Pyrite is a very dense mineral, and so fossils from this layer can be CT scanned to reveal hidden details of their anatomy. This technique involves rotating the specimen while taking thousands of X-ray images, allowing the fossils to be reconstructed in unparalleled three-dimensional detail.

“As well as having their beautiful and striking golden colour, these fossils are spectacularly preserved. They look as if they could just get up and scuttle away. Rather than representing a “dead end”, Lomankus shows us that megacheirans continued to diversify and evolve long after the Cambrian”

- Associate Professor Luke Parry, co-corresponding author (Oxford Earth Sciences)

Today, there are more species of arthropod than any other group of animals on Earth. Part of the key to this success is their highly adaptable head and its appendages that performs many functions, like a biological Swiss army knife. These can include sensing the environment and feeding. While other, older megacheirans used the great appendage for capturing prey, in Lomankus the typical claws are much reduced, with three long and flexible whip-like flagella at their end.

This suggests that Lomankus was using this frontal appendage to sense the environment, rather than to feed, indicating it lived a very different lifestyle to its more ancient relatives in the Cambrian Period. Unlike other megacheirans, Lomankus also seems to lack eyes, suggesting that it relied on its frontal appendage to sense and search for food in the dark, low-oxygen environment in which it lived.

The head of Lomankus edgecombei. Credits: Luke Parry (photograph), Yu Liu, Ruixin Ran (3D models).

“These beautiful new fossils show a very clear plate on the underside of the head, associated with the mouth and flanked by the great appendages. This is a very similar arrangement to the head of megacheirans from the early Cambrian of China except for the lack of eyes, suggesting that Lomankus probably lived in a deeper and darker niche than its Cambrian relatives.”

- Professor Yu Liu, co-corresponding author (Yunnan University)

Life reconstruction of Lomankus edgecombei. Credit: Xiaodong Wang.

This discovery offers important new clues towards solving the long-standing riddle of how modern-day arthropods evolved the appendages on their heads. These include the antennae of insects and crustaceans, and the pincers and fangs of spiders and scorpions, called chelicerae. Exactly what is the equivalent of the great appendage of megacheirans in living species has been controversial, however, the structure of the head of Lomankus favours the idea that the great appendages share a common origin with the chelicera of spiders and scorpions.

“These remarkable fossils show how rapid replacement of delicate anatomical features in pyrite before they decay, which is a signature feature of Beecher’s Trilobite Bed, preserves critical evidence of the evolution of life in the oceans 450 million years ago.”

- Professor Derek Briggs, co-author (Yale University)

The full study, ‘A pyritised Ordovician leanchoiliid arthropod’, is available to read online in Current Biology.